Building the resilience of water infrastructure in Lima Peru

Building the resilience of water infrastructure in Lima Peru

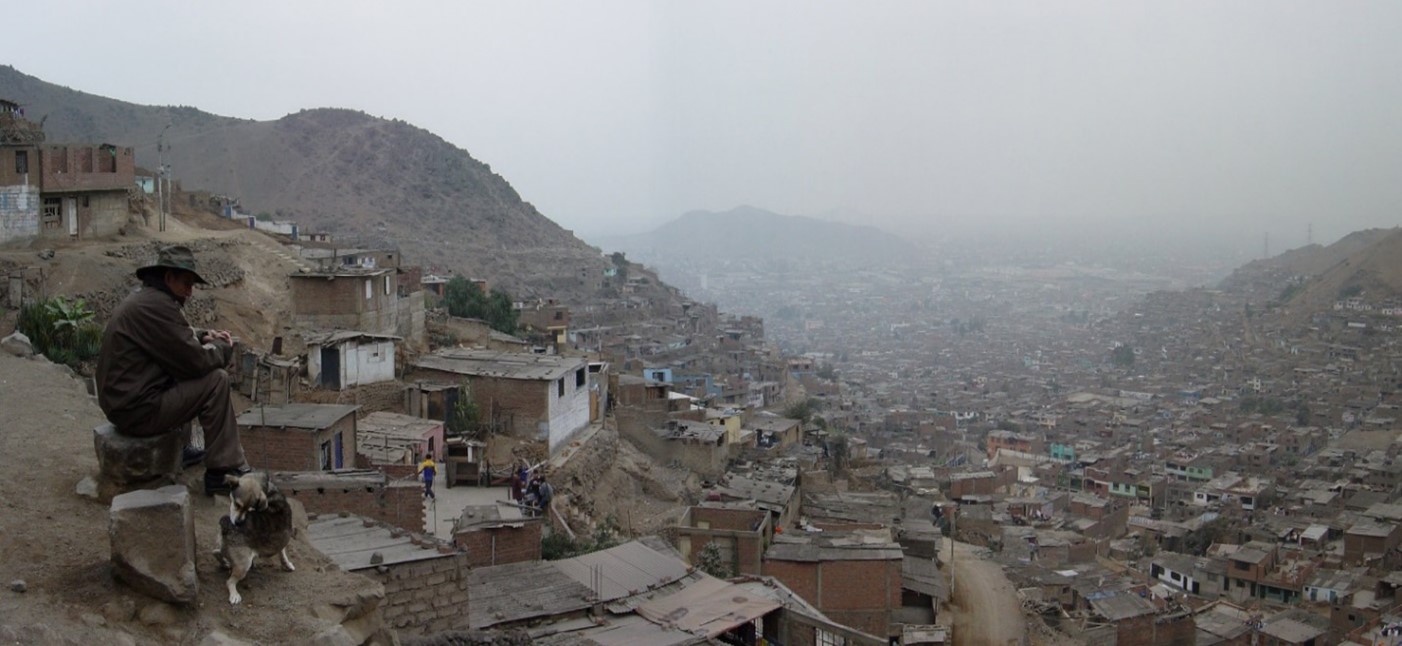

Lima is the second driest city in the world and its rapid urban expansion has further exerted pressure in the existing provision of basic services, particularly water.

By - Susana M. Rojas Williams

Lima, with close to 10 million inhabitants, is considered the second driest capital city in the world after Cairo, according to the National Environmental Council (CONAM). The main issues the city faces are water scarcity, water safety, and adequate water treatment.

Since the 1940’s Lima has experienced rapid urbanization and unplanned growth primarily through large-scale land invasions. The high costs of extending existing public infrastructure and services are straining already tight government budgets, and fewer communities and families can benefit from basic resources.

Furthermore, the Rimac, Chillon, and Lurin rivers, that supply the city are not able to meet demands, as precipitations in the Andres – where these rivers originate – are also changing with rainfall decreasing and glaciers melting. In the last 40 years the glaciers coverage reduced by 40% due to global warming (1).

Water safety is also a significant issue since river waters get significantly polluted due to mining and industrial activities along the basins. The lack of adequate solid waste management has also resulted on people dumping trash and construction waste in the rivers further contaminating the waters. Water, thus, is heavily treated by the main service provider (public enterprise) but not all have access to treated water, particularly coming from local vendors where quality control is quite inconsistent.

Key challenges identified for the water sector in Lima are - a) limited water and sanitation coverage, b) deficient maintenance and management, c) low capacity of service providers to manage water supply, d) lack of standards for sanitation interventions, e) lack of coordination among actors - particularly to coordinate investments, and f) lack of appreciation for sanitation services.

These challenges need to be addressed in order to meet global commitments, particularly: SDG Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all, as well as targets: 6.1- By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all; 6.2- By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations; 6.3 - By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally; 6.4 - By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity; and 6.5- By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate.

Addressing these challenges will also help fulfil other global commitments such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. It is critical to be able to protect and build resilience of water, sanitation, and sewage systems to reduce disruption of services due to natural or man-made disaster, further reducing the transmission of infectious diseases.

The New Urban Agenda has also called for universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water as part of the progressive realization of the right to adequate housing. Similarly, and with a focus on poverty reduction, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development, calls for the provision of basic public services for all, including water and sanitation towards ending extreme poverty. Lastly, adequate water resource management is an important contributor to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, particularly around climate adaptation and mitigation. This is particularly critical in the context of the second driest city in the world.

In order to address the water sector challenges in Lima, I chose to use the “City Water Resilience Assessment” framework developed by ARUP, the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), the 100 Resilient Cities, and the Resilience Shift with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, the World Bank, and the OECD.

I chose this framework because it is sector specific, context specific (urban), it focuses on a systems approach (looking at key linkages and relationships, problem root causes, and inter-sectorial aspects), and pays close attention to processes and people – not only to the technical aspects of water infrastructure.

Furthermore, the framework relies on a multi-stakeholder engagement process throughout all the different steps: from the preparation of the assessment (understanding the system and the key actors intervening and/ or benefiting from that system); sector assessment and analysis; the development of an action plan (co-created by all relevant stakeholders and addressing social, economic, environmental and cultural considerations); action plan implementation (including project and intervention prioritization with feasibility studies); and monitoring, evaluating and learning together.

The framework is also quite comprehensive, relying on studies, data analysis, interviews and addressing various dimensions of the water sector: leadership and strategy, planning and finance, infrastructure and ecosystems, and health and wellbeing – addressing service delivery, community empowerment and prosperity, strategy and governance, policy and regulations, integrated planning, sustainable funding and financing, effective disaster response and recovery, management and operations, resource management and environmental considerations, equitable provision of services and inclusion, and healthy spaces.

The stakeholder engagement process is consistently supported by the necessary data and information (spatial maps, system low charts, trend analysis, policy audits, demographics, analysis of existing project /programs, feasibility reports, surveys, best practices, etc.) to facilitate analysis, dialogue, co-creation, negotiation, and co-learning that can promote innovation at scale.

Based on an assessment of the water sector in Lima, with a simulated participatory process of relevant stakeholders (public, private and civil society sectors), the following recommendations are being put forward as part of a Water Infrastructure Resilience Building Action Plan. The recommendations have been organized per strategic dimensions of the water sector:

|

dimensions |

Main recommendations |

|

LEADERSHIP AND STRATEGY |

|

|

PLANNING AND FINANCE |

|

|

INFRASTRUCTURE AND ECOSYSTEMS |

|

|

HEALTH AND WELLBEING |

|

The participation of relevant stakeholders throughout all steps of the development, implementation, and monitoring of a Water Sector Resilience Strategy for Lima is key to ensuring that different perspectives are incorporated, multiples challenges are addressed, and there is buy-in and commitment by all actors involved, while also ensuring transparency and accountability.

This is also important because meaningful stakeholder engagement can also help define what the appropriate governance structure and what the roles and responsibilities - among all relevant actors - would be for the provision of water supply and related services such as sanitation and waste management. Below is a list of key actors to participate as per different sectors:

|

NATIONAL, METROPOLITAN AND DISTRICT GOVERNMENT |

|

|

COMMUNITY-BASED AND CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS |

Organized community-based organizations can provide important data, information, and feedback to ensure that all types of investments are able to meet the needs and address the constraints faced by low-income communities, particularly in informal settlements. |

|

PRIVATE SECTOR |

The participation of the private sector, especially from local service providers, is important to ensure commitment to comply with water quality standards and adequate management of water resources, while providing feedback to policies and measures. |

|

OTHER DEVELOPMENT PARTNERS |

International organizations can bring different experiences and best practices, provide technical assistance and support with resource mobilization. |

https://unfccc.int/news/peru-s-glaciers-shrink-40

Susana M. Rojas Williams is an urban planner and architect with 18-year experience in the normative and operational aspects of sustainable, inclusive, and resilient urban development, with particular focus on adequate housing, access to basic services and infrastructure investments, and access to land and tenure security.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

.jpg)

.jpg)