The Oxygen Express: How regional cooperation can help prepare for future pandemics

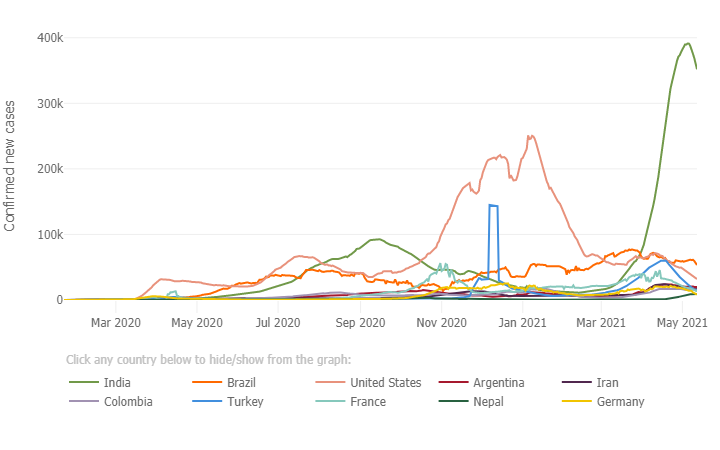

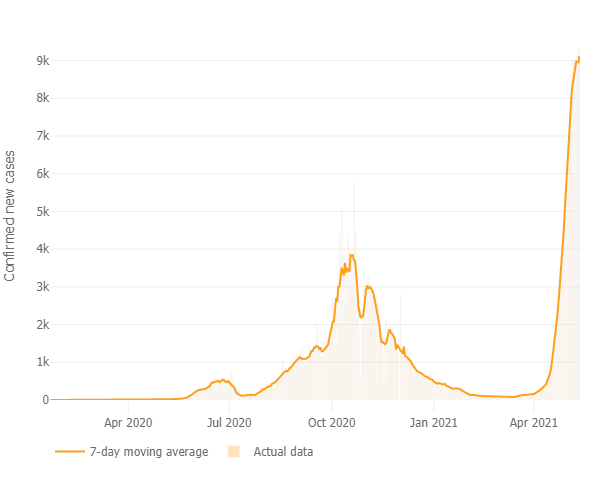

In recent weeks, India’s second COVID-19 wave has been devastating, reaching world records for the total numbers of cases and deaths and overwhelming the healthcare system. On 8 May, India, for the first time, registered more than 4,000 deaths and over 400,000 new infections in just one day. The most striking aspect of the second wave is the astronomical speed with which it grew, with daily caseloads rising from about 12,000 in mid-March to 412,000 in the first week of May. While the speed of India’s second wave is unique with over 3,200 per cent growth in cases (Figure1), a similar speed is being seen in the neighboring country – Nepal (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Daily confirmed new cases (7-day moving average): outbreak evolution for the current most affected countries (Source: John Hopkins University, Accessed 14 May 2021).

Figure 2: Daily confirmed new cases (7-day moving average) in Nepal (Source: John Hopkins University, Accessed 14 May 2021)

Oxygen is vital for patients of COVID-19 - a respiratory disease that attacks the lungs and can lead to dangerously low levels of oxygen in the body. It is so essential that it features on the World Health Organization (WHO) model list of essential medicines. Before the second wave, 700-800 tons per day of medical oxygen were required. This increased to 3,500-4,000 tons per day by the second week of April - a jump of over 400 per cent - putting immense pressure on oxygen manufacturing units in the country. A large proportion of the 238,000 deaths in the second wave are attributed to overstretched basic healthcare facilities — particularly medicinal oxygen supply.

As the pandemic threatens both the demand and supply of oxygen, India launched the Oxygen Express, backed by an innovative two-pronged strategy to address the lifesaving demands of medical oxygen.

Launching the domestic ‘oxygen express.’

To increase production, metals producers and petrochemicals plants are diverting their production to medical oxygen to meet the required daily consumption. Oxygen needs to be transported from production centers in Eastern India, to Delhi in the North and Maharashtra and Gujarat in the West (where most of the oxygen is needed). This means transporting millions of high-pressure steel cylinders, regulators, and non-sparking valves and connectors across the country. This can be challenging as cryogenic containers cannot be manufactured overnight to transport compressed liquid oxygen. Currently, multi-modal transport networks such as railways, waterways, roadways and airways are running roll on, roll off (RO-RO) rakes of truck-mounted cryogenic tankers.

The Oxygen Express of global solidarity is activated.

India has previously had a longstanding policy of discouraging external assistance in major disasters such as the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and the 2013 Uttarakhand floods. However, the current oxygen crisis has led to a shift, with the country now accepting oxygen from 40 countries, including neighbours Bhutan and Bangladesh. Humanitarian assistance is pouring in, including oxygen generation systems, distribution equipment such as cryogenic tankers, industrial and personal oxygen cylinders, and concentrators.

While the Oxygen Express is likely to cover the requirements of oxygen demand, the crisis has revealed three critical lessons in preparing for future pandemics:

1. Anticipatory actions

Although evidence indicates that a more contagious COVID-19 variant is spreading in India, the spread of the second wave is also driven by gaps in policy responses that emanate from a lack of anticipatory actions. So far, mathematical models have been used to inform public policies, including many e-social distancing measures implemented worldwide. However, all models face challenges due to data availability, the rapid evolution of the pandemic and unprecedented control measures. Strengthening mathematical modeling research capacity for pandemic planning forecast response and early warning systems will be key to support risk-informed anticipatory actions.

2. Health infrastructure services

Essential emergency and critical care (EECC), including oxygen, must be prioritized, basic and scalable. A vital lesson from this pandemic is that the capacities of public health systems must be scaled, and repurposed and systemic approaches must be used for strengthening resilience across all sectors towards disasters. Otherwise, disruptions to the supply chain systems on which various facilities and undisrupted services depend have fatal consequences.

3. Regional cooperation

As the world responds to the pandemic and many countries begin to roll out vaccination programmes, we have a unique opportunity to develop a resilient, accessible, inclusive, and affordable health and supply chain system for all. The ESCAP Resolution ‘Building back better from crises through regional cooperation in Asia and the Pacific,’ is an important step towards developing a regional strategy to strengthen post-COVID-19 health resilience in the region, building on the Bangkok Principles for the implementation of the health aspects of the Sendai Framework.

Sanjay Srivastava is the Chief of Disaster Risk Reduction at the UN Economic and Social Commission.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

.jpg)

.jpg)